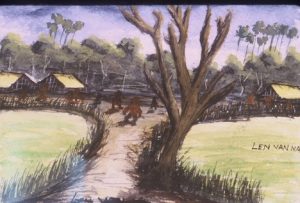

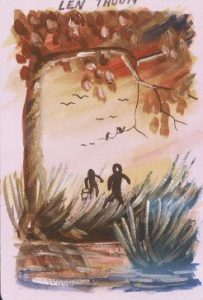

Paintings are by children at Khao-I-Dang refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border.

Sometime in 1981 I got a call from a friend, Kevin who taught courses in infectious diseases at Southwestern Medical School. He asked if I wanted “to put in some PPDs” (tests for tuberculosis). “Sure,” I said. Leslie wanted to go and we met my friend at a two-story house on Sycamore Street near the corner of Carroll and Live Oak Streets. The house was called the “Welcome House” and there were several newly arrived families from Cambodia. Refugees. They were all thin and traumatized from war, torture, concentration camps, refugee camps (which, by the way, are not nice places), and travel to this foreign land called Dallas.

Kevin and I put in the PPDs via needle just under the skin. I was struck by how quiet everyone was, including the children, even when I slipped the needle in. Meanwhile Leslie was having a good time holding a baby. I remember Leslie was wearing a pink tank-top and afterward she was captivated by the baby scent that clung to the fabric.

A day or two later the refugee agency caseworker called me sometime in the early morning. “Kao Ly, he already died” (name changed). I didn’t know what else to do so I drove to Sycamore Street. “Kao Ly” was a middle-aged man with four or five sons and a daughter. He was, in fact, lying dead in a bed he shared with several of his sons.

An ambulance took his body to the medical examiner’s (ME) office where he was held for several days for autopsy. During that time, another Cambodian family took care of the children and the caseworker arranged for them to go to another state to live with their mother. The ME was holding the father’s body I guess because they were waiting on toxicology. We wanted to have a ceremony before the children left.

Someone knew a Korean monk who was willing to hold the ceremony and that’s how we ended up on the loading dock at the ME’s facility, a several story building adjacent to the county hospital. At the time Dallas County had a population of about 1.5 million people which meant a lot of corpses processed through that building. The building smelled of death. There were Christmas lights on the dispatcher’s glass-fronted cubicle and some Pepsi cases stacked along the wall. Someone wheeled the body out, covered in a sheet up to just under the chin.

There was the body on the gurney, and beside it four desolate children and the monk wearing an orange robe. Over to the side was the refugee caseworker and me. The monk lit incense sticking up from a can with sand in it, he lit a candle, he extended a string from the body to the children with each child holding on to it, he chanted in Pali for awhile, and then he reached into his robe and pulled out a pair of scissors and he cut the string between the body and the children. It was a powerful moment in the midst of all this death and suffering.

The children went to live with their mother. I’m still in contact with several people who passed through the Welcome House when they were children, though I’ve lost touch with the family of the man who died. I know that at least several of the children from that family have done well in life.